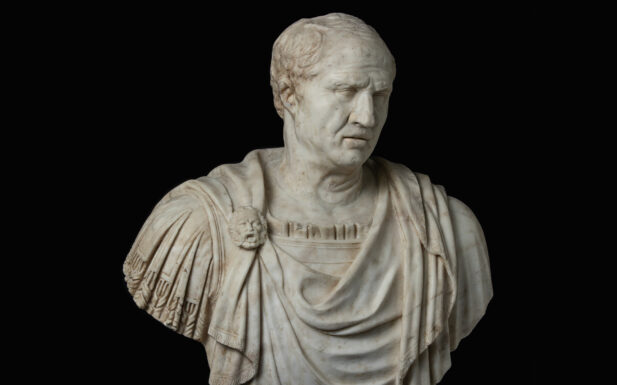

The relief presents us with the figure of Artemis: the goddess is depicted as a hunter together with her usual attributes, namely the crescent moon that adorns her head, like a sophisticated diadem, the quiver with arrows, secured to her torso by a light band across her abdomen, and the bow, which she holds in her left hand.

The fragmentary state of the work, which lacks the lower portion along a line cutting the protagonist’s thigh in half, does not allow us to identify a further element accompanying the representation: the belt clasped in the right hand must have held a dog or a deer tied to the other end, animals that often accompany the goddess, evoking her role as a hunter. On the other hand, the choice to portray the virgin completely naked, i.e. without the usual chiton that usually covers her when she is about to chase wild beasts, seems rather unusual. The image outlined in the Mantuan relief combines the dual iconography of Artemis: the latter is in fact associated with both the world of nature, and in particular hunting, and the lunar star and its powerful influence on earthly phenomena. Like her brother Apollo, god of the sun, Artemis instead dominates the night and all the dark aspects associated with it. While its arrows are a necessary tool for preying on wild animals, they also allude to the beams of light from the moon and stars.

The anonymous author of the marble has depicted the goddess in a rather unnatural position: while the face is portrayed in profile, the shoulders appear perfectly frontal, as do the breasts; the twisting of the pelvis suggests a movement of the lower limbs in the same direction as the head. Just as many uncertainties can be found in the anatomical characterisation of the figure, as can be seen in the arms with muscles similar to those of an ancient wrestler, in the cone-shaped breasts or, again, in the approximate rendering of the wrists and hands.

Donated to the Academy of Mantua by Count Giovanni Battista d’Arco, the relief was exhibited in the institution’s museum, where it was described by Matteo Borsa, in the catalogue printed in 1790, and later by Giovanni Labus, who recognised it as an ancient work. It was Carlo Ozzola who referred it to modern times and put forward the hypothesis that it might have been a creation of Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi known as l’Antico. Although the attribution to the latter sculptor has already been refuted by later critics, the association with this name nevertheless proves to be significant in order to delineate one of the main features of the work.

With Antiquity, the author of Artemis in fact shares an interest in classical relics and a desire to recreate their forms in a guise that could satisfy the tastes of patrons. We do not know if there was a precise model that inspired the work in question. What is certain, however, is that both the theme of the goddess huntress and the predilection for the bas-relief technique were able to immediately evoke antiquity and its splendours. Nor can it be ruled out that the choice of a female deity hides the commission of a woman, who would have been reflected in the virtues of which Artemis was a symbol, such as purity or chastity.